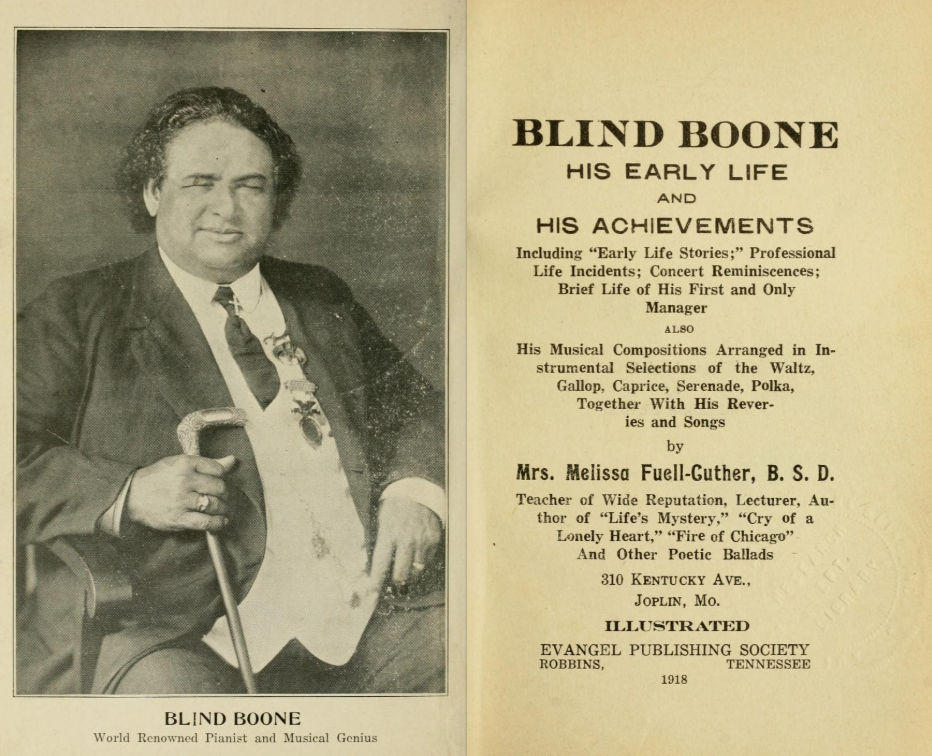

The Rediscovery Of John William Boone

by Doug Hunt

When J. W. Boone died in 1927, the administrator of his estate found that most of his wealth was gone. His wife Eugenia inherited the only the family home on Fourth Street and $132.65 in cash. Possessions that had been precious to him—his radio, player piano, and the custom-made Chickering grand piano he called “Big U”—were sold to pay debts. No headstone was placed on his grave.

Eugenia, who suffered from mental illness, kept the house on Fourth Street until her death in 1931. A newspaper reporter who crossed its threshold soon afterward saw “faded scarlet carpets, scarred light oak furniture, and tarnished gilt frames on large bright-colored pictures … all that remain to show the former glory.”

For a time memories of Boone were strong, especially in Columbia’s black community. Thanks to the generosity of a donor, the great Chickering piano found its way to the music room in Douglass School. “We understood that it was Blind Boone’s piano,” a student from the 1940s recalled, “and it was a honor to play it.” As late as the 1950s stories circulated about ghostly melodies coming from the instrument at night. By 1960, however, the piano was sitting silent in a storeroom, covered with discarded chairs, and Boone himself was being forgotten.

While the piano gathered dust, however, a few musicians were listening carefully to compositions Boone had recorded on piano rolls or published as sheet music, and they made surprising discoveries. As early as the 1880s Boone had been grafting onto European musical forms such key elements of African-American folk music as syncopation and “stride” bass lines. Such grafting would eventually produce classic ragtime and the genres that followed it: jazz, boogie-woogie, blues, and rock ’n roll. Devotees of ragtime and early jazz began to point to Boone as an innovator who helped to shape the course of American music. One of them, “Ragtime Bob” Darch, made a pilgrimage to Columbia to lay a wreath on Boone’s unmarked grave and to visit other sites associated with his life and career.

The wave of interest created by Darch’s visit encouraged the formation of the Blind Boone Memorial Foundation, which sponsored a celebratory concert on the University of Missouri campus on March 15, 1961. Part of the program featured the University’s Symphony Orchestra and Madrigal Singers performing fresh arrangements of Boone’s compositions; part featured Darch playing Boone’s great Chickering piano, restored for the occasion, while he discussed the evolution of ragtime. Included in Darch’s performance were two numbers (Strains from the Alley and Strains from the Flat Branch) that Boone had published as “Southern Rag Medleys.”

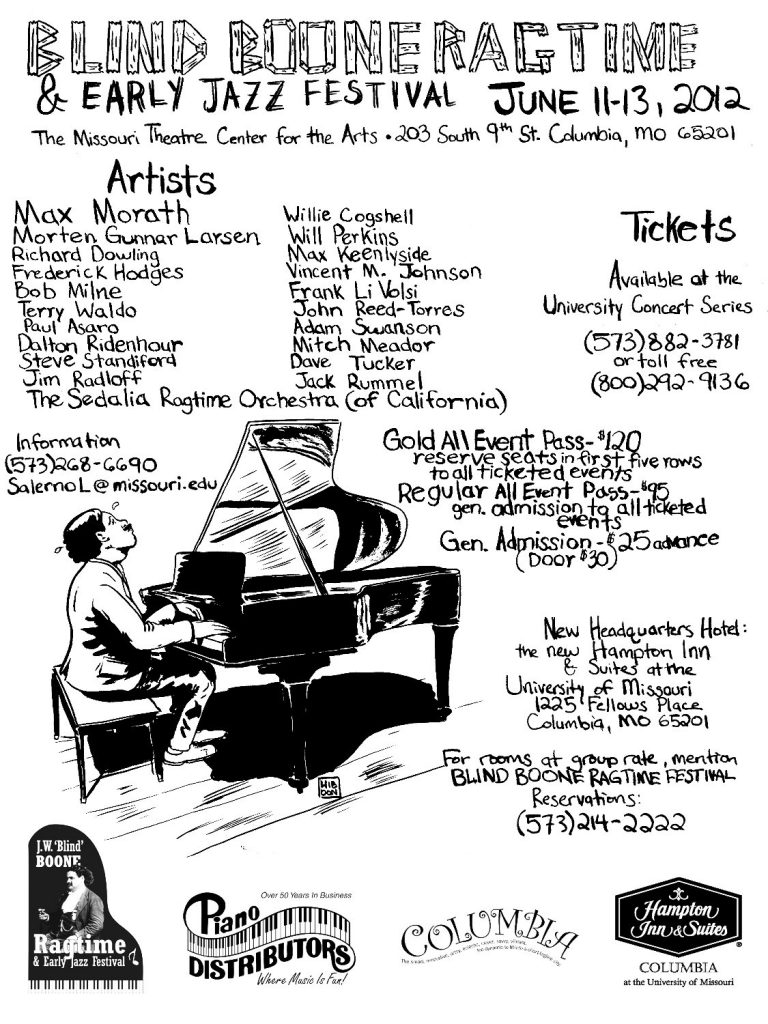

The concert drew 1300 spectators and accelerated the growth of Boone’s posthumous reputation, both local and national, as a ragtime icon. Ten years later, the Boone County Sesquicentennial Commission recognized Boone’s stature by placing a marker on the gravesite he shares with his wife Eugenia. In 1986 Columbian Jack Batterson produced a thorough academic study of the pianist’s life and career, later republished as Blind Boone: Missouri’s Ragtime Pioneer. In 1991 Lucille Salerno and others inaugurated the Blind Boone Ragtime and Early Jazz Festival, an event that would become a staple of Columbia’s cultural life for a generation, attracting performers from across the U.S. and even Europe. By the early years of the 21st century, ragtime tourists who were allowed into Boone’s abandoned home were gathering fragments of broken plaster as souvenirs.

Boone might have been puzzled by the nature of his posthumous fame. He had never considered himself a dedicated ragtimer. European composers like Beethoven, Chopin and Liszt were at the core of his repertoire. He always included at least one hymn or spiritual in a performance, and he relished the chance to “put the cookies on a lower shelf” with plantation songs, minstrel songs, and keyboard imitations of birds, trains, and musical instruments. To associate him too closely with a single genre seems to put him in too neat a box. But ragtime became the doorway through which later generations caught their first glimpses of his life and work, and it was ragtime enthusiasts like Bob Darch and Lucille Salerno whose efforts opened that door.